Biodiversity southern Africa conference, 2-6 Dec 2013 2013-12-06 (458)

The Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, held this conference this week (conference web.

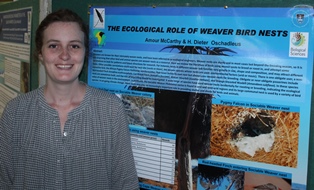

DST-NRF intern Amour McCarthy presented the following poster:

THE ECOLOGICAL ROLE OF WEAVER BIRD NESTS

Abstract. Weavers are known for their intricately woven nests, and have been referred to as ecological engineers. Weaver nests are sturdy and in most cases last beyond the breeding season, so it is not surprising that other bird and animal species use weaver nests as a resource. Here we review the literature of birds using weaver nests to breed or roost in, and attempt some correlations to look for patterns and future directions for research. For instance, nests in different weaver sub-families vary greatly in size, shape and composition, and may attract different hosts. Other possible correlations could exist for nest site (reeds or trees); the weaver species whose nests are used; environmental factors (arid or mesic). There is one obligate user, a non-passerine bird, the African Pygmy Falcon Polihierax semitorquatus, that never builds its own nest but always uses weaver nests for breeding. Obligate or near-obligate passerines include Red-headed Finch Amadina erythrocephala, Cut-throat Finch Amadina fasciata, African Silverbill Euodice cantans, and Orange-breasted Waxbill Amandava subflava. In these species nests are sometimes built, and the role of imprinting should be investigated. A wide range of species have used weaver nests incidentally for roosting or breeding, indicating the ecological value of weaver nests in the environment. In particular, the Sociable Weaver Philetairus socius is found in arid and semi-arid regions and its large communal nest is used by a variety of bird species. In on-going climate change, these nests may play an increasingly important role in providing shelter and shade for birds and animals.

DST-NRF intern Carvern Jacobs presented data on bird longevities from SAFRINGs database (including some weavers) and I presented data on my own research:

NEST BUILDING RATES IN COLONIAL AND SINGLE-MALE WEAVER COLONIES

Abstract. Weavers are known to be colonial, although some species are solitary nesters. Cape Weavers Ploceus capensis and Southern Masked Weavers P. velatus are colonial to varying degrees. Cape Weavers have colonies of 1-20 males, while Southern Masked Weavers may have several males in a colony in rural areas but usually are found in single-male colonies. Both species are polygynous and individual males build many nests to attract several females in a breeding season. It is not known how nest building rate, a costly exercise, varies with colony size. In this study male Cape and Southern Masked Weavers were observed regularly to track every nest built. All but one male was colour ringed. The study site was along a 332 m stretch along the Ottery River in Phillippi, Cape Town, from July 2012 to May 2013. Initially a patch of bamboos contained one mixed species colony of 2 male Cape Weavers and 2 male Southern Masked Weavers. Three downstream colonies had a single Southern Masked Weaver male each, with nests in exotic trees or typha reeds. Later in the season, a male Cape Weaver joined the bamboo colony, and a Southern Masked Weaver male moved from a single-male colony to the bamboo colony. There was no difference in average nests built per month in single-male colonies compared to the multi-male, multi-species colony. Thus colony size does not appear to affect nest building rates of individual males. The male Southern Masked Weaver that moved from his colony into the multi-male colony, however, increased his own nest productivity. Individual nests lasted for a very varied rate, from 1 to 246 days, the minimum values indicating that near daily observations are required for any study of nest building rates in weavers.

|